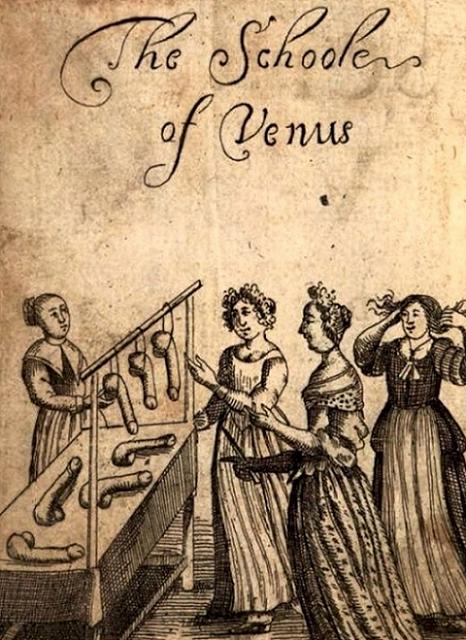

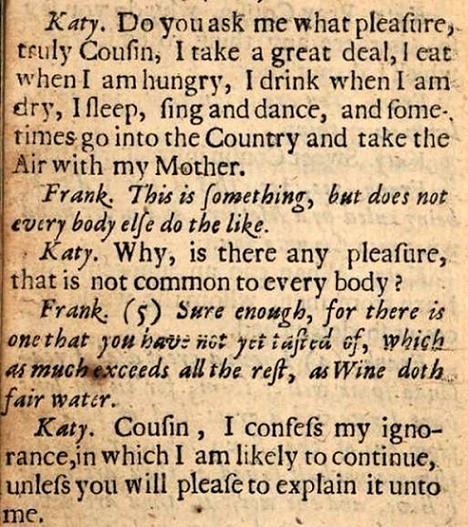

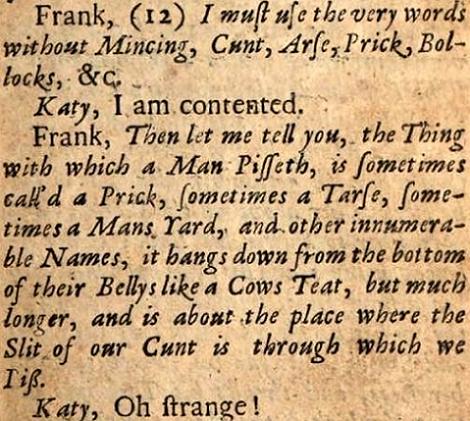

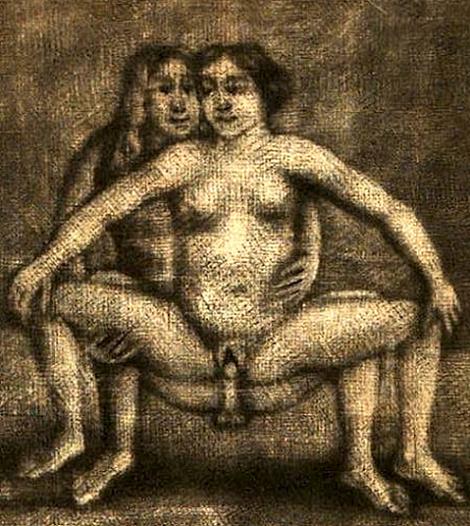

A Sex Manual from 1680 “This Misterie of Fucking” “[I] stopped at Martin’s, my bookseller, where I saw the French book which I did think to have had for my wife to translate, called L’escholle des filles, but when I come to look in it, it is the most bawdy, lewd book that ever I saw… I was ashamed of reading in it.” Samuel Pepys, the famous womanizer and diarist, was certainly no prude. This is a man, let’s remember, who brought his telescope to church so he could enjoy “the great pleasure of seeing and gazing at a great many very fine women” and who famously detailed his numerous extramarital affairs in a mixture of Spanish, French and Italian. So what was the book that made even Pepys blush? It turns out to be a surprisingly modern exploration of sexuality written in the form of a dialogue between a teenage girl and her more experienced cousin. Originally written in French and published in English in 1680 as The School of Venus, or the Ladies Delight Reduced into Rules of Practice, the anonymous book’s frontispiece engraving made its subject matter clear: The 166-page text, which has been digitized by Google Books, opens with a pseudo-dedication to one “Madam S— W—,” which lauds “with what eagerness you perform your Fucking excercises” and imagines “a Pyramide of those standing Tarses [penises]” to rival “that Monument of Sculls erected, by the Persian Sophy in Spahaune.” Poetic stuff. The main narrative then begins, introducing its two principle characters: Katherine, “a Virgin of admirable beauty” and “a Kins-Woman of hers named Frances.” Frances “come[s] to chat” with Katherine one morning, finding her alone and working “as if it were a Nunnery.” Frances reproaches her cousin for being “such a Fool [as] to believe you can’t enjoy a mans company without being Married.” Katherine naively explains that she enjoys the companionship of many men (“my two Unkles, my Cousins, Mr. Richards and many others”) but Frances explains that she means something altogether different (note that the early modern ‘s’ can sometimes look like an ‘f’): Frances reveals that even Katy’s parents indulge in “this mistery of Fucking,” and not necessarily with one another (she speculates that “your Father had often his pleasure of your Maid Servant Margaret” and that “your Mother herself” might have “some private friend”). Next, we’re treated to a seventeenth-century explication of the male and female anatomy: This isn’t exactly advanced-level sex education, but Frances does use some vivid language, memorably likening the scrotum to “something like a Purse” containing “Bollocks… not much unlike our Spanish Olives.” The School of Venus punctures some common notions about pre-modern European sexuality, which is too frequently dismissed as ‘Puritanical.’ Although the book was a product of a misogynistic and male-dominated society, it is surprisingly frank about female sexual autonomy. Katy almost immediately begins wondering “why should not ones Finger yield a Wench the like pleasure” as a penis. Soon after, Frances speculates about the societal benefits that would result “if Women govern’d the world and the Church as men do.” Female multiple orgasms are referenced throughout, and there appear to be a few scattered allusions to the clitoris (referred to as “the top of the Cunt” which “stands out.”) Some of the language in the text is also surprisingly modern, as when Frances advises her to acquire “a Fucking friend… one that will not blab” and Katy worries about how “to break the Ice” with Mr. Rogers, the friend with benefits she has in mind. At page thirty-four, the text shifts gears into a full-fledged sex manual. Popular consciousness seems to associate pre-modern sex with the missionary position, but Frances extolls the benefits of variety: sometimes my Husband gets upon me, and sometimes I get upon him, sometimes we do it sideways, sometimes kneeling, sometimes crossways, sometimes backwards… sometimes Wheelbarrow, with one leg upon his shoulders, sometimes we do it on our feet, sometimes upon a stool. The dialogue ends, well, with a bang. A series of crude mezzotints illustrate the various positions suggested by Frances: “Sometimes Wheelbarrow, with one leg upon his shoulders…” “It is pretty hard to learn it all.” “Having his Prick in my hand, I guided.” “Let him rather incline to Lean than Fat, his Hair of a dark Brown and long enough to Curl upon his Shoulders.” So what do we know of this book’s history? Scholars ignored texts like these throughout much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but since the 1980s historians of sexuality and gender have engaged with The School of Venus. James Turner’s Schooling Sex argues that the book is part of a larger “educational fantasy in sexual writing” which bounds female sexuality by a “set of male-ordered ‘rules.’” Turner also uncovers the publication history of the book, which was “simultaneously prosecuted to extinction and flaunted in the most public places.” He notes that Pepys came across the book “in a conspicuous and crowded bookshop” and that purveyors of these types of works were not shady smut-peddlers, but mainstream booksellers who stocked a range of works including scientific texts and sermons. Annamaire Jagose argues that School of Venus fails to mention the clitoris specifically, but cites a contemporary midwifery manual written by one Jane Sharp that describes it as “the seat of lust.” There’s a lot more to analyze here—toward the end, Frances describes women who will wait “until they feel the sperm coming, when immediately they will fling their rider out of the Saddle” and men who “tye a Pigs Bladder to the Top of their Pricks,” and claims dubiously that “they must both spend [orgasm] together to get a Child.” But that will have to wait. Look for a more in-depth exploration of early modern sexual manuals in a future issue of The Appendix. A small postscript about Samuel Pepys. In typical fashion, Pepys overcame his embarrassment and returned three weeks later to purchase the book, reasoning that “it was not amiss for a sober man once to read over to inform himself in the villainy of the world.” And read it over he did: Pepys skipped church the next day to peruse it in his study, noting in pseudo-Spanish that “it did hazer my prick para stand all the while.” He burnt it immediately afterward. |

|

Instructions For American Servicemen In Britain, 1942 Instructions for American Servicemen in Britain is a fascinating and occasionally hilarious guide written for GIs headed to Britain—then half-ruined by war—in 1942. Subjects range from common-sense basics (“instead of railroads, automobiles, and radios, the British will talk about railways, motor-cars, and wireless”) to subtle social pitfalls regarding race, sex and income. You can read it online for free (http://www.hardscrabblefarm.com/ww2/britain.htm)

The following are some choice excerpts. The British don’t know how to make a good cup of coffee. You don’t know how to make a good cup of tea. It’s an even swap. The British are often more reserved in conduct than we. On a small crowded island where forty-five million people live, each man learns to guard his privacy carefully-and is equally careful not to invade another man’s privacy. If you are invited to eat with a family don’t eat too much. Otherwise you may eat up their weekly rations. The British are used to this [monetary] system and they like it, and all your arguments that the American decimal system is better won’t convince them. A British woman officer or non-commissioned officer can and often does give orders to a man private. The men obey smartly and know it is no shame. For British women have proven themselves in this war. They have died at the gun posts … When you see a girl in khaki or air-force blue with a bit of ribbon on her tunic–remember she didn’t get it for knitting more socks than anyone else in Ipswich. The British have seen a good many Americans and they like Americans. They will like your frankness as long as it is friendly. They will expect you to be generous. Don’t be misled by the British tendency to be soft-spoken and polite. If they need to be, they can be plenty tough. The English language didn’t spread across the oceans and over the mountains and jungles and swamps of the world because these people were panty-waists. The British have theaters and movies (which they call “cinemas”) as we do. But the great place of recreation is the “pub.” |

|

Very Interesting Story About Monopoly Starting in 1941, an increasing number of British Airmen found themselves as the involuntary guests of the Third Reich, and the Crown was casting about for ways and means to facilitate their escape.

Now obviously, one of the most helpful aids to that end is a useful and accurate map, one showing not only where stuff was, but also showing the locations of ‘safe houses’ where a POW on-the-lam could go for food and shelter. Paper maps had some real drawbacks — they make a lot of noise when you open and fold them, they wear out rapidly, and if they get wet, they turn into mush. Someone in MI-5 (similar to America ‘s OSS ) got the idea of printing escape maps on silk. It’s durable, can be scrunched-up into tiny wads, and unfolded as many times as needed, and makes no noise whatsoever. At that time, there was only one manufacturer in Great Britain that had perfected the technology of printing on silk, and that was John Waddington, Ltd. When approached by the government, the firm was only too happy to do its bit for the war effort. By pure coincidence, Waddington was also the U.K. Licensee for the popular American board game, Monopoly. As it happened, ‘games and pastimes’ was a category of item qualified for insertion into ‘CARE packages’, dispatched by the International Red Cross to prisoners of war. Under the strictest of secrecy, in a securely guarded and inaccessible old workshop on the grounds of Waddington’s, a group of sworn-to-secrecy employees began mass-producing escape maps, keyed to each region of Germany or Italy where Allied POW camps were regional system). When processed, these maps could be folded into such tiny dots that they would actually fit inside a Monopoly playing piece. As long as they were at it, the clever workmen at Waddington’s also managed to add: British and American air crews were advised, before taking off on their first mission, how to identify a ‘rigged’ Monopoly set — by means of a tiny red dot, one cleverly rigged to look like an ordinary printing glitch, located in the corner of the Free Parking square. Of the estimated 35,000 Allied POWS who successfully escaped, an estimated one-third were aided in their flight by the rigged Monopoly sets. Everyone who did so was sworn to secrecy indefinitely, since the British Government might want to use this highly successful ruse in still another, future war. The story wasn’t declassified until 2007, when the surviving craftsmen from Waddington’s, as well as the firm itself, were finally honored in a public ceremony. It’s always nice when you can play that ‘Get Out of Jail’ Free’ card! |